In an aged patient in a forgotten village, time seems to move quite unlike the restless rhythm of city life. As if the hands of the clock never indeed measure hours but instead trace the eternal return of the same cycle. There we see the ebb and flow of seasons, with lives and deaths, with triumphs and defeats. After all, we witness the story of Putulnaacher Itikatha as an intimate portrait of resignation, rebellion, and chiefly, the eternal human struggle against the weight of one’s roots.

The village of Gaodiya, with its twisting, half-concealed alleys and towering banyan tree with branches that span several generations, becomes the living pulse of the film. It is a place whose stillness mirrors that of its people, who are as much prisoners of tradition as they are of their own desires. Among these people is Dr. Shashi, a man forged in the crucible of Western education, who returns with the hope of an outsider who believes that reason can guide the course of human lives. However, with the unfolding of his entry into this world, every one of his hopes seems to break against the ancient stones of this place.

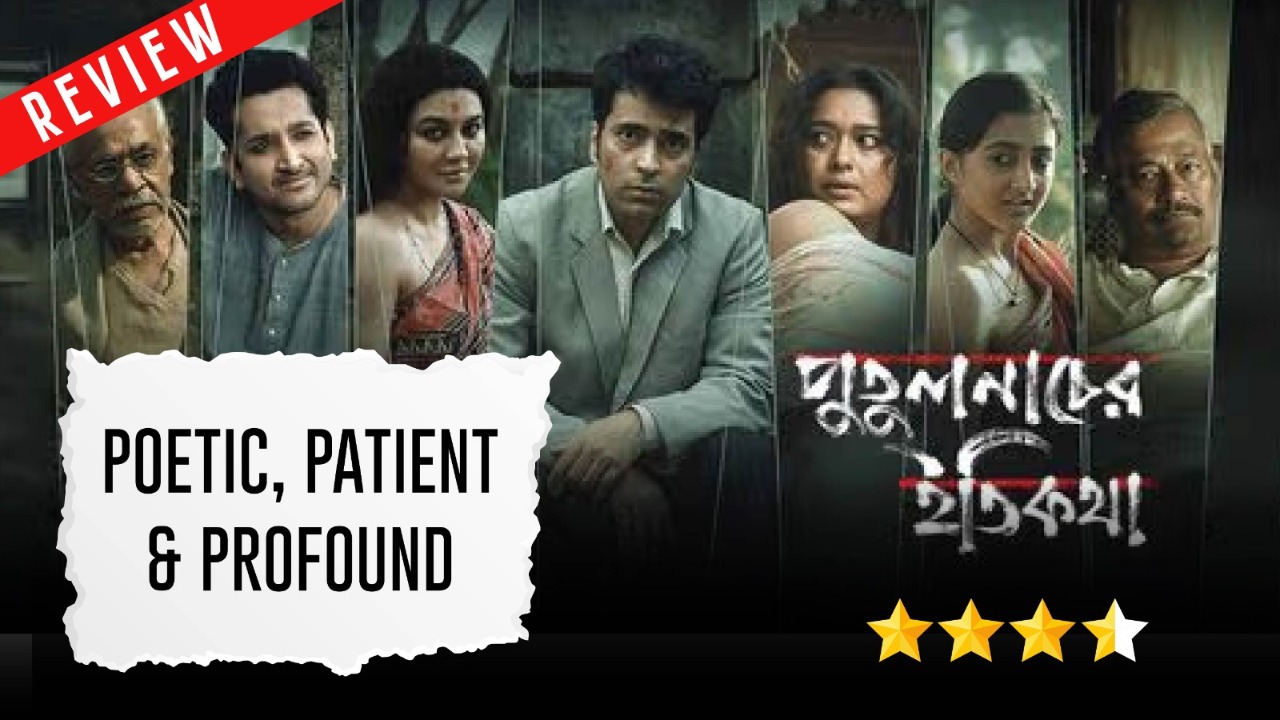

Putulnaacher Itikatha, directed by Suman Mukhopadhyay and produced by Kaleidoscope Entertainment, is a narrative not marked by loud confrontations but by a lingering, painful silence. For Dr. Shashi, played with quiet intensity by Abir Chatterjee, the struggle is internal, marked not by dramatic speeches but by the isolation he endures in the presence of those who seem so rooted in their ways, so unable to leave behind the weight of their ancestors’ thoughts.

In the story, the contradictions in the world are represented by the characters. The obstinate Jadab Pandit (Dhritiman Chatterjee), a man whose roots are as deep as a banyan tree, represents an ancient wisdom that cannot die, at least not with reason. He scoffs at Shashi’s modernity, yet they have a connection, a respect, hidden beneath layers of belief. With him, we see the elasticity of belief, and the stubbornness with which old certainties die.

Then there is Sen Didi (Ananya Chatterjee), whose beauty once commanded the gaze of every villager, now slowly withering beneath the scar of smallpox. She is the epitome of a society that values appearance over essence, where even the scars of disease are seen as marks of disgrace. Her struggle to reclaim her beauty, while her soul remains untouched by Shashi’s medical touch, speaks to a more profound, existential yearning: the desperate need to hold onto something that is slowly slipping through one’s fingers.

But it is Kusum, portrayed with understated brilliance by Jaya Ahsan, who becomes the film’s pulse. The widow, the childless woman, the one whose very existence defies the traditional roles imposed on her, Kusum is a reflection of the complex dance between the individual and society. At once playful and deeply melancholic, she embodies the tension between desire and despair, between the craving for love and the knowledge that, in this world, it is always fleeting. Her longing for Shashi, her subtle flirtation, is not just the yearning of a woman, but the yearning of a soul caught between possibility and impossibility.

The rustic atmosphere of Gaodiya is like its own character. The still river, the thickness of the banyan tree, the fog moving across fields like egress of faded memories, all succumb to the awe-inspiring poetics of creation filtered through cinematographer Sayak Bhattacharya’s lens. In the noted scene of Shashi’s anguish in the boat, with Haru’s corpse before him, the fireflies flicker almost to remind us that even as we grapple with death, there is still somewhere along the way with life in death and death in life. The rhythms of nature reflect the characters’ inner worlds, drawing a parallel to the inevitability of suffering in humans and nature’s inevitable continuum.

But the brilliance of Mukhopadhyay’s vision lies in his refusal to offer easy answers and clean resolutions. This is not a film about the triumph of reason over superstition or love conquering isolation; it is about the very quiet collapse of hope. The lives of the villagers, seemingly clinging to tradition and the lure of strange old myths, are filled with secret longings and unspoken desires, along with the choking awareness that they are caught in their own trap.

The performances in Putulnaacher Itikatha are sublime by every measure. Abir Chatterjee’s Shashi is the very image of restrained despair-a man torn between two worlds, his feet side-by-side in neither. Dhritiman Chatterjee infuses Jadab with the wisdom of age and the bitterness of one who knows intolerance approaches yet is unwilling to give in to it. Ananya Chatterjee portrays Sen Didi with that very real fragility of a woman ill-treated by her beauty and now left to negotiate among the shards of her self-worth. And of course, Jaya Ahsan as Kusum, where every look and every movement reveals the woman who comprehends the impermanence of her own being, caught between the desire for love and the crushing weight of societal expectation.

An even deeper realisation strikes us: life itself is the sorrowful culmination of things that we have lost; that the sadness lies truly in losing. The film neither praises death nor romanticises suffering. We are, instead, invited to witness the quiet humiliation of painful acceptance of what actually is: the inevitability of tradition grasping hold, or the slow erasure of the self from memory under other people’s expectations.

Putulnaacher Itikatha is not about the triumph of one over tradition. And just like that, you come to concede that the absolute freedom is not in breaking the cycle, but in accepting its eternal turning.

IWMBuzz rates it 3.5/5 stars.